The Canon of Scripture, Part 2

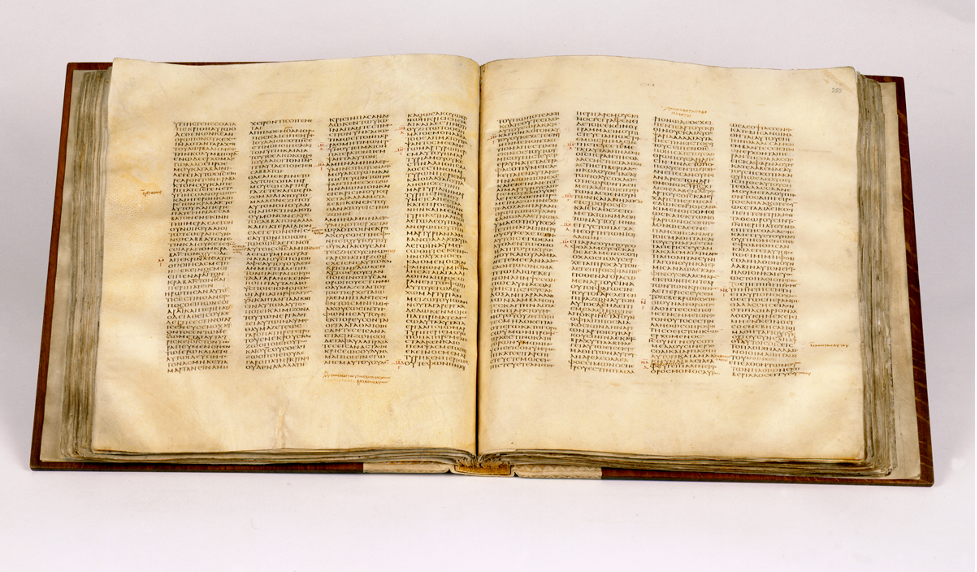

Codex Sinaiticus , c. 350 A.D.

British Library, London.

[This is one of four great uncial codices, handwritten copies of the Christian Bible written in Greek. It is the oldest complete copy of the New Testament, suggesting that the New Testament canon was fixed by the mid-4th century. Codex Sinaiticus consists of over 400 large leaves of vellum (380mm x 345mm) on which is written about half of the Greek Old Testament (the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew text, including the Deuterocanonical books, or the “Apocrypha”) and all of the New Testament, although the New Testament books are in a somewhat different order from that of modern Bibles.]

(Listen to an audio version of the blog post above!)

In “The Canon of Scripture, Part 1” we learned how a religious canon develops and how the books in it became viewed as “sacred writings.” Now, in “The Canon of Scripture, Part 2,” we’ll learn how the individual books of Scripture entered into the canon.

The Hebrew Scriptures (or “Old Testament”)

Thanks to the conquests of Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.) and his successors, Koine Greek (“common” Greek) became the lingua franca of the ancient Near East, lands stretching from Asia Minor in the north to Egypt in the south, and from Macedonia in the west to modern-day Afghanistan and India in the east. Hellenization was so successful that most of the peoples in those lands embraced it wholeheartedly. A fairly large number of Jews in the East resisted the trend, however, producing the Babylonian Talmud in Hebrew and Aramaic during the 6th century A.D., but most embraced the culture and language of the Greeks wholeheartedly. In the west—particularly in Alexandria, Egypt, and north into Judah and Jerusalem—Hellenization became so complete that Hebrew was all but forgotten and Greek became the written language of literate Jews.

Since the Hebrew Scriptures were not accessible to Hellenized Jews, the Hebrew Scriptures needed to be translated into Greek. The pseudo-epigraphical “Letter of Aristeas” is a story telling how that translation came to be. The Egyptian king, Ptolemy II (285-247 B.C.), wanted Demetrius of Phalerum, his librarian, to collect all the books in the world for his great library at Alexandria. Demetrius thought that such a collection should include the Jewish Law in a Greek translation, so he ordered a letter to be written to the high priest in Jerusalem. In the letter, he suggested that six members of each of the twelve tribes be involved in the translation, a suggestion that was accepted by the high priest, and the 72 men were sent to Alexandria, where, after a sumptuous banquet, they set to work on their translation. Miraculously, the 72 men completed the final draft of their translation in precisely 72 days! After being reviewed by the Greek-speaking Jewish community in Alexandria, curses were pronounced on anyone who should change the translation in any way, asserting that the translation was “canonized” as the official Greek version of the text.

Although the rather fanciful story tells us that 72 men worked as translators and completed their work in 72 days, the Alexandrian Greek translation became known as the “70” (or LXX, “Septuagint” in Latin), perhaps recalling Exodus 24: 1, 9 where we read that 70 elders accompanied Moses up Mt. Sinai to receive the law and the commandments from God. This original Septuagint translation in the mid-4th century B.C. included only the five books of Moses (the Torah): Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy; by that time these books had been firmly established in Judaism as sacred canonical writings. The “Prophets” (Nevi’im) and the “Writings” (Ketuvim) were added to the Septuagint over time, as were other books written in Greek, including those we call the Deuterocanonical books (or “Apocrypha”): Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch and the additions to Daniel and Esther, as well as the Psalms of Solomon, 3 & 4 Maccabees, Letter of Jeremiah, Book of Odes, the Prayer of Manasseh and Psalm 151, which were included in various copies of the Septuagint.

Importantly, the Septuagint—the “Bible” that Jesus and the Apostles knew—was not yet a closed canon at the time of Jesus and the early church. As nearly as we can tell, there was no established “canon” of Scripture at all in Second Temple Judaism prior to A.D. 70, no authoritative list from which books could be added or subtracted. And that makes sense, because codices were just emerging, pages gathered between two covers: what we would call a “book.” All of the Old Testament writings were on individual scrolls, so apart from the Torah, they were not viewed as clearly defined “sets” or “collections.” In addition, while there were authoritative writings gathered into loosely defined groups—“the Law, the Prophets and the Psalms,” as Jesus said in Luke 24: 44—these categories remained open for quite some time, for the writing of sacred works—or scripture—was not seen as being limited to the distant past: witness the advent of Jesus and the Christian scriptures, which emerged from Second Temple Judaism.

In Jesus’ day and throughout the 2nd and 3rd centuries, there were hundreds of synagogues scattered throughout the Roman Empire, and there was no single governing body overseeing their operation. Consequently, there was a great deal of latitude in what one community viewed as “scripture,” versus what other communities viewed as “scripture.” So, an Old Testament canon did not begin to emerge until we move into the 2nd century A.D., but in Jesus’ day it was much more amorphous.

The New Testament

Jesus wrote nothing. Not a book. Not a letter. Not a laundry list. Jesus’ entire public ministry involved oral teaching and preaching, validated by miraculous healings. It was left to his disciples—the Apostles and others who followed—to write his story and to implement his desire that the “gospel message” be proclaimed to the very ends of the earth. That was done, not by writing books, but by oral teaching and preaching, as Jesus had done.

As we have seen, books—in an age when each book had to be laboriously hand-copied—were a very expensive and inefficient way to disseminate information. Jesus could sit on a hillside, perched a half-mile west of Capernaum, and preach to a crowd of 5,000 people; St. Paul could stay in Ephesus, the major deep-water port on the west coast of Asia Minor, and within three years “all the inhabitants of the province of Asia heard the word of the Lord, Jews and Greeks alike” (Acts 19: 10), as a result of St. Paul’s teaching and preaching to travelers passing through. As we have already noted, books were a very inefficient way of spreading the Gospel. Besides, there was no need to write a book, for virtually every 1st-generation Christian believed that Jesus would return within his or her lifetime to usher in a new kingdom, the Kingdom of God. Books enshrined words for the ages, elevating them to the sacred; but the gospel message was urgent, a message for now.

The earliest Christian writings are those from St. Paul, and his letters and epistles were occasional; that is, they were written for a specific audience or purpose, not for the church at large. The earliest were probably 1 & 2 Thessalonians, written during St. Paul’s second missionary journey, shortly after arriving in Corinth (c. A.D. 50-52). St. Paul probably wrote Galatians at the same time, since he had passed through Galatian territory at the beginning of his second missionary journey. Galatians also addresses specific issues in the newly-formed Galatian churches, chiefly that of other teachers passing through and preaching a “different gospel” than the one St. Paul had preached. Indeed, all of St. Paul’s epistles—Romans, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 & 2 Thessalonians, as well as his personal letters, 1 & 2 Timothy, Titus and Philemon—are occasional, addressing immediate problems or concerns. They were not meant to be theological treatises, works written for the ages. The same is true for Hebrews, James, 1 Peter and 1, 2 & 3 John. Second Peter is the only epistle addressed to the church at large and meant to have universal, timeless application; it was written sometime between A.D. 64-68, while St. Peter was awaiting execution in Rome, cooling his heels in the Mamertine prison.

The Gospels are another story entirely. Jesus had said to his Apostles, “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you” (Matthew 28: 19-20a), he did not tell them to go write books; he told them to preach and teach, as he had done. Jesus’ message was urgent, for as he said in the Olivet Discourse: “Amen, I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place” (Matthew 24: 34). As we have already noted, everyone in the 1st-generation church expected Jesus to return during his or her lifetime.

But, when the early to mid-60s arrived two things happened: 1) Those who were eyewitnesses to Jesus’ teaching and preaching, to his death, burial and resurrection were aging, and many had already died; and 2) the first state-sponsored persecution against Christians began in Rome, directed by the Emperor Nero, A.D. 64-68. Both Peter and Paul were caught in the net and were martyred. It is impossible to know how many Christians were martyred in Rome between A.D. 64-68, but the aging, eye-witness population and Roman persecution served as catalysts for the story of Jesus to be written down lest it be lost, seeing as how Christ had not yet returned and the eye-witnesses were quickly disappearing.

Mark was probably the first gospel written, sometime in the early to mid-60s; Matthew followed, probably in the late 60s; and Luke appeared in the early to mid-70s. The three are known as the synoptic gospels (Latin, synopticus; Greek, sunoptikovß], “seen with the same eye.” John, knowing that Matthew, Mark and Luke were in circulation in the Christian communities, did something entirely different with his gospel, sometime in the late 80s or early 90s. Of course, many other works were written in the centuries that followed. Like the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, hundreds of New Testament “Apocrypha” emerged, giving accounts of Jesus and his teaching, stories of the Apostles, and musings on God and the lives of the Saints. Such works were commonplace in the early centuries of the Church, works like the Apocalypse of Peter (c. A.D. 175-200), offering a vision of heaven and hell, granted to Peter by Jesus; the Gospel according to Judas (c. A.D. 280), which claims that Judas was not a betrayer at all, but that he carried out Jesus’ specific instructions; and the Gospel according to Thomas (c. A.D. 340), not a narrative of Jesus’ life, but a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus. You can read the New Testament Apocrypha here: Wilhelm Schneemelcher, ed. New Testament Apocrypha, rev. ed.; English translation ed. by R. McL. Wilson, 2 vols. (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1991). So, which of these works would make it into the New Testament canon?

There were many lists of New Testament canonical writings, beginning in the second century. Four of these are particularly important:

Possibly the earliest of these is the Muratorian fragment (c. A.D. 170-270). It includes the four gospels; Acts of the Apostles; all thirteen of St. Paul’s epistles and letters; Jude; two letters of John, and Revelation. Missing are: Hebrews; James; 1 & 2 Peter; and one letter of John. Added are: the Apocalypse of Peter and the Wisdom of Solomon (!).

In the first half of the fourth century (c. A.D. 300-350), the church historian Eusebius offered a list that included twenty-two books, omitting as “disputed”: James, Jude, 2 Peter and 2 & 3 John;

Cyril of Jerusalem (A.D. 350) listed all 27 books of the current New Testament, except Revelation.

Finally, in A.D. 367 Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria sent his annual letter to the churches in his diocese. This 39th Festal Letter contained a definitive list of the 27 books that would become the canon of the New Testament, as we know it today.

As we can see, the lists of books included in the New Testament were more or less consistent, although there were some disagreements. The standard for inclusion seems to have been two-fold: 1) a book was attributed to an Apostle or someone closely associated with an Apostle; and 2) it was written during the first generation of the Church. Under the influence and direction of St. Augustine, the list of 27 books given by Athanasius of Alexandria was codified at the Council of Hippo in A.D. 393, affirmed at the Council of Carthage in 397 and re-affirmed by Pope Innocent I in A.D. 405.

But back to the Old Testament. As we have seen, the Old Testament canon remained open during the time of Jesus and the formation of the 1st-generation Church. Many books written in Greek, Aramaic and Coptic were used by both Jews and Christians throughout the Roman Empire. In the 1st century A.D., the Church was predominantly Jewish, but by the end of the 2nd century A.D. Gentiles made up the vast majority of believers. For Christians at that time, the Hebrew Scriptures (or the Old Testament) had its greatest value not in how it illuminated Jewish history, destiny and self-understanding, but in how it foreshadowed or “pointed to” Christ, especially as Gentiles became more and more prominent in the Church.

Consequently, by the time we get to St. Augustine and the Council of Hippo in A.D. 393, a “Christian” canon of Old Testament Scripture had begun to take shape, based upon those books in the Septuagint that Jesus would have known, those books that foreshadowed Christ and those that were efficacious for teaching about Christ. Codex Sinaiticus, a Greek manuscript written between A.D. 330-360 in beautiful uncial script [which you can see at the top of this blog], is one of the two earliest complete copies of a Christian Bible. Codex Sinaiticus was discovered by Constantine von Tischendorf in 1844 at St. Catherine’s monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai. The text of the Old Testament is that of the Greek Septuagint, and it includes all of the Deuterocanonical books, plus the Shepherd of Hermas and the Epistle of Barnabas. Its New Testament includes all 27 books. Codex Sinaiticus, along with Codex Vaticanus (A.D. 300-325), offer a snapshot of the Christian canon as the monastic scribes understood it in the mid-4th century, shortly before St. Augustine proposed his canon in A.D. 393 at the Council of Hippo:

St. Augustine’s list includes 44 books. With Lamentations and Baruch, which are included under Jeremiah, the list totals 46 books, the same 46 books that were translated into Latin by St. Jerome and others as the Latin Vulgate, which became the Bible of Christendom for the next 1,000 years. That is a long and very distinguished pedigree, an important criterion for affirming canonical status. Indeed, these are the same books that were affirmed as canonical at the fourth session of the Council of Trent on April 4, 1546; the same books that were affirmed by Vatican Council II’s Dei Verbum on November 18, 1965; and the same books that are included in all Roman Catholic bibles—the canon that includes the Deuterocanonical works of Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Esther & Daniel.